Showtime’s Black-Cast Drama Had Hearty Helping of Reality

By Ovetta Wiggins

Washington Post Staff Writer

When we recently left our favorite couple on “Soul Food,” Teri was waking Damon up from a drunken stupor. He said he needed to use the bathroom. She said they needed to talk.

Have it your way, he said, then proceeded to irrigate her potted plant.

The next morning, Damon (Boris Kodjoe) was packing his Escalade as a rejected Teri (Nicole Ari Parker) went back inside the house they once shared. And, in typical “Soul Food” fashion, as the credits rolled, Nancy Wilson was crooning “I Can’t Make You Love Me.”

A little melodramatic, yes. But that’s what Showtime’s highest-rated original series brought its faithful followers every Wednesday night: a lot of what Mary J. Blige said she wanted no more of — drama.

But that’s certainly not the tune that regular “Soul Food” followers will be singing tonight as television’s longest-running black drama airs its series finale at 10.

They want more of the drama that the Joseph sisters brought weekly into their living rooms.

Drama that includes, among other things, an alcoholic loved one, a child who scores low on a school aptitude test and another who struggles with fitting in at a predominately white private school.

Drama that has resonated with “Soul Food’s” mainly female, 18-to-49-year-old audience. They are people who have had a relationship ruined because of alcoholism, or who have had a child with a reading disability, or a family member who is an ex-convict trying to turn his or her life around.

“I’ve been getting a lot of e-mails and letters from viewers, saying what am I going to watch now?” says producer Tracey E. Edmonds, of Edmonds Entertainment Group Inc., who brought the characters from the 1997 movie of the same name to Showtime. “I ran into people of all colors who said they were tuning into the show saying it reminded them of issues they dealt with in their families or in their relationships.”

Any faithful watcher of “Soul Food” will tell you that the show took viewers to a place that television rarely if ever ventures.

Into the world of black folks.

Not the slapstick version seen on the handful of black comedies that have found a home on most networks.

The real world of black middle-class America. Or as close to it as television can, or has ever tried to, get.

Unlike “The Cosby Show,” the groundbreaking NBC comedy that on some level transcended race, “Soul Food” embraced its blackness.

“[‘Soul Food’] shows you the diversity of black life in America,” says Julia Clarke, a teacher in New York who has hosted a couple of “Soul Food” parties. ” ‘The Cosby Show’ was about this super-educated family with a doctor and a lawyer and all their kids striving . . . basically blacks pursuing the white dream. This is about black people living.”

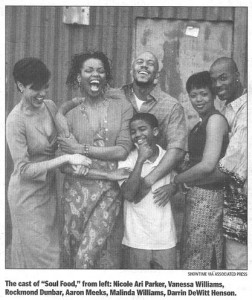

The series, set in Chicago, gave a realistic, frank and, at times, funny look into the love lives and family relationships of Teri, the career woman who wanted to fix everyone else’s problems; Maxine (Vanessa Williams), the wife and mother who dabbled in poetry and politics; and Bird (Malinda Williams), the baby sister who ran her own beauty salon.

The series, which ran for five seasons, picked up where the movie (starring Nia Long as Bird and Vanessa Williams — no relation to the TV actress — as Teri) left off, after the death of Mama Joe, the strong-willed mother who raised a tight-knit African American family, always bringing her family together for its traditional Sunday dinner.

“It was almost a no-brainer for it to be successful,” said Kathleen McGhee-Anderson, the show’s executive producer. “There is an unmet appetite for stories, well-told stories, about African Americans.”

McGhee-Anderson, a former film editor for ABC News and assistant professor of film at Howard University, said Showtime allowed the writers to “be courageous . . . we could tell risky stories, talk about behavior that is natural and real.”

There was the story line about married men who live on the “down low” (have affairs with men). The one about the recuperation of Maxine’s husband, Kenny (Rockmond Dunbar), after a near-fatal car accident.

Where else on television but “Soul Food” could you find a story line about a parent’s worry that her teenage son, who showed a preference for “light-skinned girls with wavy hair,” was “color struck”?

“Soul Food” writers took on the sensitive subject of light- and dark-skinned blacks, an issue that has plagued African Americans for more generations than we care to remember, by having Maxine introduce her son, Ahmad (Aaron Meeks), to her friend’s daughter with hopes that the two would go to a school dance together. Ahmad thinks Noni (who is dark-skinned) is cute until he meets her cousin, Amina (who is light-skinned).

Maxine questions what her son sees as beautiful. Is her son like the boys who rejected her for girls with a lighter complexion?

“Have you ever noticed how light-skinned all Ahmad’s girlfriends are?” Maxine asks her husband, Kenny. “It just seems like he doesn’t like dark-skinned girls.”

Maxine, a dark-skinned woman sporting dreadlocks, remembers struggling with her own color complex because her older sister, Teri (“Daddy’s light-skinned little princess”), was always given what she wanted.

“I’m going to make sure my baby isn’t giving into self-hatred,” Maxine says.

Kenny reassures Maxine but also warns her that Ahmad, who attends a mainly white private school on voucher, might one day marry a white woman.

“The kids at his school are either white or biracial,” Kenny says. “We gave him those options.”

“I just want him to remember he got a brown-skinned mama,” Maxine says.

Robert Thompson, director of the Center for the Study of Popular Television at Syracuse University, says “Soul Food,” which won a few NAACP Image Awards, “never got the attention that it deserved based on its quality.” The season began with 1.2 million viewers, but declined to 508,000 by last week’s episode.

As we enter the final episode, Bird has decided that she wants to have another baby with her husband, Lem (Darrin DeWitt Henson), the ex-con, who strove to be the father that he never had.

Maxine and Kenny are enjoying the money they made from selling the family-owned towing company. But the two are bickering about whether they should invest it by starting a counseling center (Maxine’s choice) or a classic car restoration business (Kenny’s idea).

And then there’s Teri. She’s been asked to open an Atlanta branch of the high-profile Chicago law firm where she was named a managing partner. Now she has the opportunity to become a senior partner. But it means leaving her sisters.

“It’s a chance to have my name carved in granite as a senior partner of Burke Willis,” she tells Maxine and Bird.

Maxine wonders what will happen to their family.

“She can’t find a good man in Chicago; maybe she’ll have better luck in Atlanta,” Bird says.

Or should she take a man with her to Atlanta?

“She can’t,” says Pauletta Handy, a Bowie resident who says she subscribed to Showtime only to get her fill of “Soul Food.” Handy says Teri is too career-driven for Damon. “He has a poor track record of being stable,” Handy says. “In the end, it wouldn’t work out. She would get bored with him and he’s too insecure for her.”

Handy says she may need to buy some flowers as a way of saying goodbye to a group of people who have been in her life for the past five years.

She wonders when television will bring her another show that will satisfy her the way “Soul Food” did.